‘Iraq is the big oil prospect,’ began the minutes of a meeting at the Foreign Office on 6 November 2002. ‘BP are desperate to get in there.’ The tone was unusually expressive for the notes of a government meeting: civil servant minute-takers normally manage to find blandness in even the most far-reaching discussions.

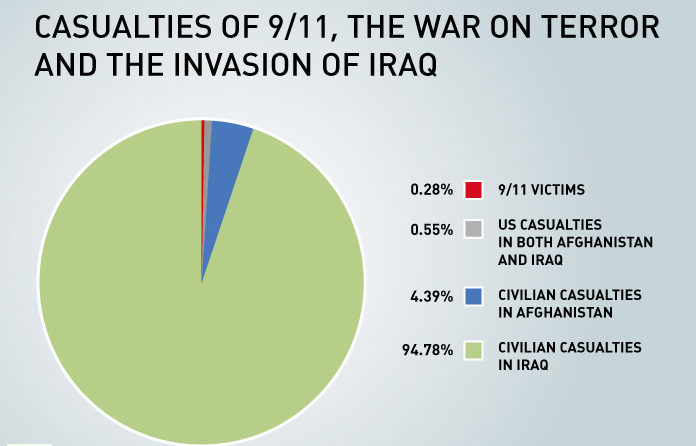

Four months later, a war would begin that would cost hundreds of thousands of lives, and destroy a country. But with about ten percent of the world’s oil beneath its soil, for BP Iraq meant business.

That meeting was one of five in which the Blair government discussed Iraq’s oil with BP and Shell, in the run-up to the war. The companies denied any such meeting took place; it was years later that the meeting minutes were obtained and revealed in the book Fuel on the Fire by Greg Muttitt, which tells the full story of how throughout the war and occupation, BP and Shell kept their eyes on the prize.

As further documents reveal, the companies worked closely with the British government, an occupying power, to shape Iraq’s oil policy in their interests.

In 2004, BP hired Sir Jeremy Greenstock, who had been Britain’s administrator of southern Iraq. The Advisory Committee on Business Appointments instructed Greenstock not to do business in Iraq for six months. But just three months later, he and his new BP boss, John Browne, jointly met Iraqi Prime Minister Ayad Allawi to lobby for BP.

Meanwhile, the revolving door swung the other way as Terry Adams, former head of BP Azerbaijan, was hired by the UK government to write Iraqi oil policy, and to help transfer the publicly-owned oil production into the hands of companies like BP.

Well before the war, recognizing the political sensitivity, Shell had a team working on a country called “East Jordan”. It entered a partnership with an Australian company that had gained oilfield rights from Saddam Hussein in a tainted deal in violation of sanctions.

When BP, Shell and four other oil companies engaged an organization to lobby for them highly profitable contracts, the UK government helped arrange meetings with Iraqi ministers.

Rob Sherwin, a former Shell official was hired by the Foreign Office in 2005 to coordinate Middle East energy policy. When asked whether Iraqis should be consulted before privatizing their most valuable asset, he demurred, arguing that Iraqis might get too “emotional” and oppose the privatisation.

Eventually in 2009, long-term contracts were offered to multinationals. The Iraqi government was little more than a puppet, consisting of UK and US allies who’d had no administrative experience before the occupation put them in power. So they needed to be trained in oil negotiations. The training provider? BP.

In a public auction two months later, BP won a contract for Rumaila, Iraq’s largest oil field. But even this was not enough, so over the following months, BP entered a private negotiation with the Iraqi oil minister, unsupported by civil servants. The result was a contract much more favourable to BP. Soon after, Shell won major contracts too.

Fifteen years after the war began, Iraq is today a broken country. Public institutions have collapsed, poverty increased, and many lost their lives and homes. Because at their heart the war and occupation were designed to serve oil interests above all.