In February 2020, BP announced with a fanfare its ambition to become ‘net zero’ by 2050. That might sound like an impressive about-turn for one of the world’s biggest polluters. But while in some ways it’s a step in the right direction, sadly that’s all it is; BP’s ‘ambition’ is full of loopholes and doesn’t go anywhere near far enough – or fast enough – to curb climate breakdown. In fact, the absolute emissions from the products BP sells will continue to grow until at least 2030.

What we need is a rapid, managed decline of oil and gas extraction down to actual zero, that protects workers and frontline communities as part of a just transition. What we don’t need is to be still producing fossil fuels in 2050 – which is what BP plans to do.

With this change of focus, BP is trying to reinvent and rebrand itself as part of the solution, a climate leader that can be trusted to set the pace and scale of its own transition away from fossil fuels. This is incredibly dangerous, because its ultimate aim is to protect its profits, not the planet. As long as BP remains an oil and gas company, it’s vital that we continue to challenge its power and influence, and not give it a seat at the table.

10 problems with BP’s ‘Net Zero’ claims:

- Missing the target

- Picking, choosing and ignoring Rosneft

- It’s not all about production

- New oil and gas exploration

- Net zero is NOT zero

- The fantasy of carbon capture

- Offsetting responsibility

- Selling off assets is NOT leaving fossil fuels in the ground

- Not ‘Paris aligned’, not science aligned

- Climate virtue signalling?

1. Missing the target

BP has been careful to say it has ‘an ambition’ to reach net zero – not a binding target. The term ‘target’ has legal implications for companies like BP because it communicates to investors that there is a concrete plan in place that it can be held accountable to. Setting ‘an ambition’ or ‘goal’ might sound similar but amounts to PR tactic that allows BP to claim its business is now aligned with the Paris Climate Agreement while making no binding commitments to cut emissions at the rate the science demands. Exactly what the pathway all the way down to net zero looks like for the company is still unclear. And anywhere you find BP giving details of its ‘net zero’ ambition, it will be accompanied by this ‘cautionary statement’: ‘Actual results may differ materially from those expressed.’

As if to prove this point, when a group of shareholders, co-ordinated by Follow This, tabled a resolution for the company’s 2021 Annual General Meeting calling for these ambitions to be turned into binding targets aligned with the Paris Agreement, BP recommended that shareholders vote against it.

2. Picking, choosing and ignoring Rosneft

BP’s promotion of its ‘ambition’ strongly implies that it will now make the whole of its business net zero. But in reality, BP is picking and choosing how it will apply to different parts of its business. BP has set itself 5 aims for “transforming” its business – but it’s really only the first three that directly address the question of how it might reduce its currently vast levels of emissions. The first is the only one that applies to both the upstream business (what it produces) and downstream business (what it refines and sells): to make its own day-to-day operations ‘net zero’.

BP’s second aim sounds impressive on paper though: to make its oil and gas production net zero by 2050. And as a first step, BP has announced that it will cut its production by 40% by 2030. But there are some major loopholes here.

What BP doesn’t highlight is that it isn’t counting around one third of its actual production – all the fossil fuels it gets through its 19.75% stake in the massive Russian state oil firm Rosneft. So that production cut figure is really around 27% – far short of the cuts we need to be seeing from major Western oil companies to have any possibility of keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees.

3. It’s not all about production

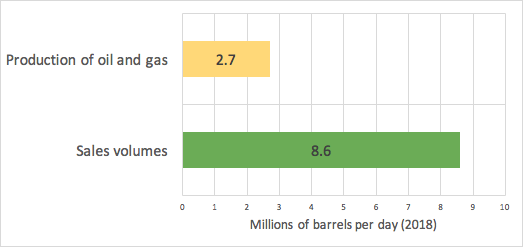

BP sells a lot more oil and gas than it actually produces itself – and this isn’t being made ‘net zero’. According to the Financial Times, the fossil fuels that BP sells accounts for:

‘more than half the total, with its sales volumes reaching 8.6m barrels a day in 2018, while its production of oil and gas totalled 2.7m barrels of oil equivalent a day…’

For all the oil and gas that BP buys from others, refines and then sells on, it has set the much more flexible third ‘aim’ of ‘halving the carbon intensity’ of those products. This measure means that, in practice, the actual volumes of oil and gas BP sells could remain high as long as they are ‘balanced’ by increased sales of renewable energy and dubious carbon offsets (see section 7).

It also means that, as BP has itself admitted, the absolute emissions from the products the company sells will actually continue to grow until at least 2030.

4. New oil and gas exploration

One of the most underwhelming elements of BP’s ‘net zero’ ambition is that it says it will undertake ‘no exploration in new countries’. Another way to phrase this would be it can ‘keep exploring for new sources of fossil fuels in the 79 countries it already operates in’. BP does not intend to stop looking for more oil and gas to extract around its existing finds, even though there is already far more carbon in the reserves we already know about than we can afford to burn. A credible plan to transition away from being a fossil fuel company would accept that there is a finite carbon budget and therefore not undertake any new oil and gas exploration.

Instead, BP plans to invest $9 billion in 2021 in its oil and gas business, and is pursuing some incredibly destructive projects, including:

- BP’s Russian partner, Rosneft, in which it owns a nearly 20% stake, is pushing ahead with a vast $134bn new project in the Arctic. The Vostok project aims to produce 100m tonnes of oil a year.

- BP is a partner in Burrup Hub, a mega fossil fuel project proposed in Western Australia involving the development of two giant new gas fields and other oil and gas resources. If it proceeds, it will be the most polluting project ever developed in Australia.

- BP has now begun deliveries of gas from the Shah Deniz field in the Caspian Sea – the site of its largest ever gas find – to Europe via the Southern Gas Corridor. The second phase of production is under way which is adding 16 billion cubic metres of gas a year, with plans to increase this even more.

- BP remains involved in fracking in Argentina’s massive Vaca Muerta shale fields, despite huge local opposition to this highly carbon-intensive and ecologically destructive process, including from Mapuche Indigenous communities.

5. Net zero is NOT zero

The word ‘net’ needs to be treated with extreme scepticism when fossil fuel companies claim they are going ‘net zero’. BP does not plan to completely stop producing or selling oil and gas by 2050. Instead, it aims to either remove or offset the emissions it does produce so that it can say that it has become ‘carbon neutral’. BP’s CEO Bernard Looney has claimed that:

‘whatever hydrocarbons are left [in the company’s portfolio in 2050] will be decarbonized through various means. Through carbon capture, through hydrogen, through natural climate solutions. There are tools in the toolbox.’

There are many problems with this approach. As the report ‘NOT ZERO: How ‘net zero’ targets disguise climate inaction’, from a group of climate justice organisations, puts it:

‘Far from signifying climate ambition, the phrase “net zero” is being used by a majority of polluting governments and corporations to evade responsibility, shift burdens, disguise climate inaction, and in some cases even to scale up fossil fuel extraction, burning and emissions… At the core of these pledges are…promises of technologies that are unlikely ever to work at scale, and which are likely to cause huge harm if they come to pass.’

6. The fantasy of carbon capture

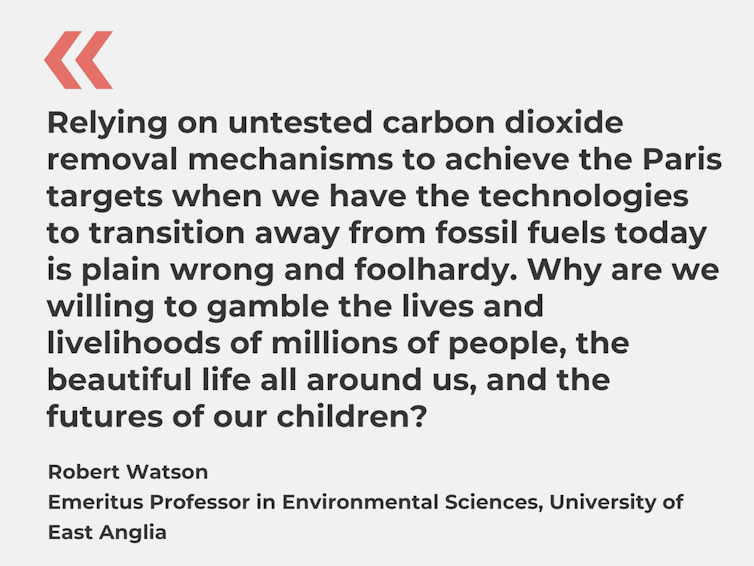

As highlighted above, a big part of BP’s ‘net zero ambition’ rests on the idea that it will be able to capture and store large amounts of the carbon it emits from its fossil fuels in the future, so that it doesn’t contribute further to global heating. But at the moment, such claims are wildly unrealistic.

Despite billions in public funding over the last decade, the world is currently capturing and storing a mere 0.01% of all greenhouse gas emissions. As of 2020, only 26 plants with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) are in operation globally, despite the technology existing for over twenty years. 22 of these 26 existing CCS plants are being used for ‘enhanced oil recovery’ – rather than simply being stored, the carbon dioxide is pumped into wells to extract hard-to-reach oil. This makes the process financially viable, but of doubtful benefit to the climate.

In November 2020, 41 leading scientists publicly busted 10 myths about net zero targets and carbon offsetting, saying:

‘[Carbon capture] technologies are being developed but they are expensive, energy intensive, risky, and their deployment at scale is unproven. It is irresponsible to base net zero targets on the assumption that uncertain future technologies will compensate for present day emissions.’

These ‘tools’ are far from the simple, readily available solutions BP’s CEO is making them out to be. Even if carbon capture were to become realistic at the kind of scale BP would require, it will be *much* cheaper, simpler, safer and more equitable to leave the fossil fuels in the ground and transition to clean energy instead.

7. Offsetting responsibility

As highlighted earlier, BP CEO Bernard Looney has said that BP will get to net zero by using ‘natural climate solutions’. What he is referring to here is carbon trading and offsetting. And this is hugely controversial. It involves tree-planting on a vast scale, and the trading of ‘carbon credits’ so that carbon emitted can be theoretically ‘cancelled out’ by carbon saved elsewhere.

This approach is ineffective for several fundamental reasons:

- carbon offset markets are based on flawed assumptions and have largely failed so far to actually reduce net carbon emissions

- offsetting schemes do not negate all the negative impacts of fossil fuel extraction

- there is simply not enough available land on the planet to accommodate all of the combined corporate and government ‘net zero’ plans for offsets and tree plantations.

The ‘NOT Zero’ report warns that if carbon offsetting happens on the scale being suggested by the fossil fuel industry,

‘Rural farming and Indigenous communities in the global South are likely to be pushed off their land. As a result, unprecedented landlessness, hunger and food price rises would disproportionately affect people and communities that have done little to contribute to climate change, further compounding the already deep injustice of the climate crisis.’

BP is a strong advocate of this concept though because it allows it to continue extracting fossil fuels while claiming to be cutting emissions. It has been running the ‘BP Target Neutral’ offsetting scheme for years, and in December 2020 bought a controlling stake in Finite Carbon, the largest US forest carbon offset developer.

Importantly, carbon emissions are not the only harmful environmental impacts of fossil fuel extraction: the ongoing ecosystem damage caused to the Gulf of Mexico by BP’s record-breaking Deepwater Horizon oil spill a decade ago, or the toxic impacts of a spill of BP fuel off the coast of Mauritius last summer are clear examples of why we also need to transition away from extractivism.

8. Selling off assets is NOT leaving fossil fuels in the ground

Part of BP’s new strategy is to significantly increase its investments in renewable energy, which has drawn a lot of praise. However, what has been overlooked is that it is raising the funds for that investment by selling off existing fossil fuel assets, which allows them to still be exploited by other companies while BP is able to say it has cut its emissions. This is not the same as leaving those fossil fuels in the ground, which is what needs to happen. For example, in February 2021 BP sold a 20% stake in an Oman gas block for $2.6bn to Thailand’s national oil company, part of a plan to eventually sell off £25 billion of assets this way. But that just ensures that those fossil fuels will still get extracted and burned, without BP having to take responsibility for their emissions.

What we need to see is more ‘writing down’ of fossil fuel assets by BP, in order to make sure they stay in the ground forever. And if BP won’t do this out of choice, we urgently need governments to step in and declare a permanent moratorium on new oil and gas developments, as Denmark has recently done.

9. Not ‘Paris-aligned’, not science-aligned

BP claims that its new approach is ‘consistent’ with the international Paris climate agreement, and therefore implies that it is reducing its emissions in line with what the climate science requires. This is misleading on both counts. The Paris Agreement includes a commitment to ‘pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’. This is absolutely necessary to aim for in order to avoid catastrophic impacts across the world, particularly for Indigenous communities and small island nations. But the actions that governments and corporations have so far signed up to in the name of Paris do not get us anywhere near to that target. BP’s ‘net zero ambition’ sits firmly within that category.

So what does the science say oil and gas companies need to be doing if we are to keep global temperatures as close to 1.5 degrees as possible? BP’s 27% production cut is less than a 3% reduction per year, and its emissions in other areas will reduce more slowly, which just doesn’t go far enough. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 ºC finds that CO2 emissions must be halved within this decade. It sets out a pathway in which oil and gas use must decline by 42% by 2030 and by 85% by 2050, compared to 2019 levels. To have the best chance of staying within 1.5ºC, which takes account of tipping points and feedback loops and doesn’t rely on large amounts of tree-planting or unproven technologies to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, we should probably aim to cut emissions significantly faster. Yet BP still plans to sell oil and gas in 2050, well beyond the point at which fossil fuels should be all but phased out.

The Climate Action 100 report, which assesses publicly available information on polluting companies’ progress towards the Paris goals, recently found that BP failed to fully meet any of its criteria. Even if you judge BP’s announcements by the less-ambitious Paris target of ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels’, BP falls short. The Transition Pathway Initiative has found that no oil company making net zero commitments, including BP, is “on track to align their emissions with a 2°C climate pathway by 2050”.

As one of just 20 companies who’ve contributed a third of all global emissions, BP has a huge responsibility to shift away completely from the ongoing harm it’s causing. But that’s not profitable enough, so instead it’s going much less far, and hoping to get away with it.

10. Climate virtue signalling?

It is good that BP is committing to cut its oil and gas production and admitting to having billions in ‘stranded assets’ that are no longer commercially viable due to their climate impacts. But is BP suddenly a ‘climate leader’? That’s a clear no. BP is responding to changing market conditions and dressing this up as climate leadership because it knows that’s smart branding.

At the start of 2020, the oil industry was already in crisis. Price wars between Saudi Arabia, Russia and the US and the plunging cost of renewables and electrified transport was causing oil supply to outstrip demand. Meanwhile, a resurgent global climate movement and powerful frontline resistance saw pipelines being cancelled and the political power of fossil-fuel companies whittled away by divestment and anti-sponsorship campaigns. The end of the oil age was already in sight – and then the Covid-19 crisis accelerated the process further.

The oil industry is now in unstoppable decline, but this is not a managed or fair transition to a green economy. With the fracking industry in chaos and tar sands in huge trouble, thousands of jobs are being lost, with workers bearing the brunt of the impacts of government and corporate short-sightedness.

Faced with this landscape, BP appears to have made a careful calculation. Rather than pretend that a return to business-as-usual is possible, the company has decided to spin the slow-motion collapse of its portfolio as a purposeful shift to a greener future. Costly, high-risk extraction projects can now be sold off or dumped in the name of a low-carbon transition while it expands its investments in renewables to claim a bigger stake in the industry that’s rapidly expanding to replace it. Meanwhile, this supposedly caring company continues to give legitimacy to repressive regimes in order to protect its fossil fuel interests everywhere from Egypt to Azerbaijan to West Papua.

BP’s CEO has been clear that:

‘BP is going to be in the oil and gas business for a very long time. That’s a fact.’

And that’s the problem. BP wants to persuade us that it can be trusted to do the right thing on climate change, but, ultimately, it is a profit-driven corporation whose core business is based on a product that needs to be rapidly phased out. If we leave the job to BP we are in big trouble.

As Oil Change International concludes in ‘Big Oil Reality Check’, their extensive September 2020 survey of the climate pledges made by oil companies so far:

‘Governments, investors, and communities should not assume the industry most responsible for causing the climate crisis will do its fair share to solve it. Governments in particular must step in to manage the decline in fossil fuels, by phasing out fossil fuel production and implementing Just Transition measures.’